Earmarks have been called “the best known, most notorious, and most misunderstood aspect of the congressional budgetary process.” These government budget items allocated to specific people, places, or projects are alternately described as a subversion of democracy or an important negotiation tool to smooth the passage of controversial legislation. But despite the attention earmarks attract, they remain extremely tedious and time-consuming to identify in federal bills and reports that may be hundreds of pages long.

This summer, Data Science for Social Good fellows Matthew Heston, Madian Khabsa, Vrushank Vora, and Ellery Wulczyn and mentor Joe Walsh, working with Christopher Berry at the Harris School of Public Policy, will help shine a light on earmarks, building computational tools to automatically identify them in Congressional texts.

On its face, earmarking appears to be a cheat code against democracy, taking away the power to distribute federal funds from agencies and their competitive or merit-based selection processes and giving taxpayer money directly to well-connected people and companies. In one infamous example, the “Bridge to Nowhere,” Congress allocated $398 million in federal funds to build a bridge that would connect an island with 50 residents to mainland Alaska.

But earmarks may also benefit democracy. Members of Congress believe that they understand the need of their districts better than unelected bureaucrats in Washington. They argue that earmarked projects fail to receive funding through the typical competitive process because the bureaucrats making the decisions use the wrong criteria to judge the projects.

Furthermore, earmarks have occasionally facilitated the passage of controversial legislation. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 may not have passed if Senator Carl Hayden did not receive support for a water project in Arizona. Some have argued that Congress has passed fewer bills in recent years because of tighter rules on earmarks.

Yet earmarks remain difficult to identify and study. Not only are there slightly different definitions for the term, but earmarks can be introduced in many ways. Members of Congress can insert earmarks in the text of an appropriations bill, the explanatory report attached to the bill (where as much as 95% of earmarks reside), or call or write the bureaucrats who make budget decisions in an attempt to steer money to a favored project.

Congressional bills are often long and dense, making it difficult for the reader to understand what they contain, so they can take a long time to read. Yet bills often go up for a vote before anyone has a chance to thoroughly review them. The Congressional leadership recently gave members less than a week to review a 1,600-page appropriations bill and less than 48 hours to review a 959-page farms bill before voting. Members of the public who wanted to contact their legislators about the content of those bills had even less time for review.

Finally, earmarks have become more difficult to find. Since 2010, Congress has officially banned earmarks to increase transparency and oversight. But members of Congress request earmarks anyway, and many of those earmarks make it into law. Some earmarks have gone underground; instead of inserting them into the text of the bill or its accompanying report, members of Congress are calling and writing federal agencies directly to influence the allocation of money.

Although more people can help analyze text faster, humans are costly tools, and many watchdog groups such as Citizens against Government Waste struggle to find adequately large staff to do the work. These problems compound if we want to understand how and when members of Congress insert earmarks. Tackling bill dynamics requires us to look at several versions of the same document, which multiplies the amount of text that human coders need to parse. Computers may be able to extract useful information more quickly and cheaply than existing, human-based methods.

For all of these reasons, there is a need among the advocacy and research communities to dissect Congressional bills quickly and cheaply. To speed up this process, the DSSG team will create algorithms and methods to automatically identify earmarks in congressional texts. The DSSG fellows will use text mining algorithms to automatically identify “earmark” spending not only in congressional bills, but also within congressional reports.

To build this system, it must first be trained with known earmark data. The Office of Management and Budget compiled earmarks databases for legislation from 2005, 2008, 2009, and 2010 and publishes this information available online. These databases will provide examples to train machine learning classifiers about earmark spending. First, the entries in the OMB database need to be matched with the exact location of earmarks inside bills and reports. Then, the money allocation and organization involved in the earmark need to be identified and paired together. These pairs are what our new classifier will predict.

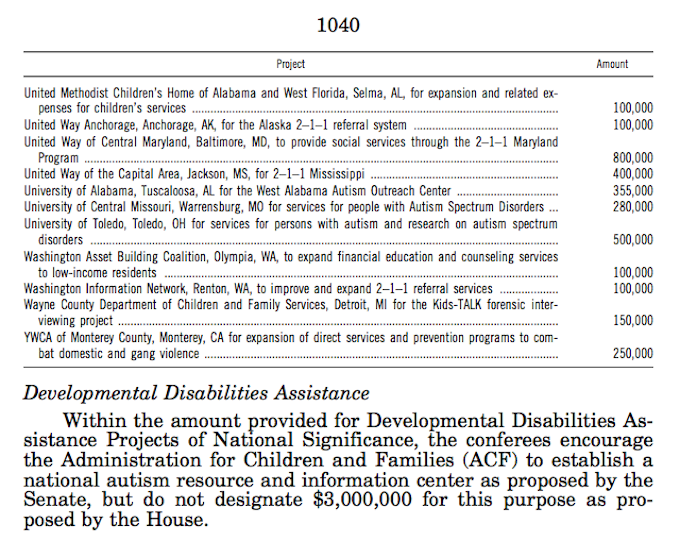

Once trained, they can analyze new bills and reports not already present in the OMB data. All named entities, such as organizations, need to be identified from paragraphs in the bill text, and more often, tables in the congressional reports. Similarly, money allocations must be detected, and later matched with a detected named entity. We are using off-the-shelf Named Entity Recognizers (NER) such as OpenCalais to identify entities inside bills, and a special recognizer we developed to parse tables within reports.

[An example table of earmarks in a Congressional report.]

[An example table of earmarks in a Congressional report.]

Once the classifier locates pairs of organizations or projects and money allocation within the text, it will then predict whether that pairing qualifies as an earmark. Some false positives may include when the identified organization is a federal agency properly qualified to distribute funds, when an allocation is erroneously paired with the wrong organization, or when the classifier mis-identifies text as an organization, such as the abbreviation “Sec” instead of the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC).

At the end of the summer, the team hopes to share its methods and algorithms with the world, and hopefully donate a database of automatically-identified earmarks. Such a database would be a valuable first step to understanding the nature of earmarks. Not only would it shed light on when and where earmarks are being inserted; it might also enable us to better estimate the effect that earmarks have on our government and economy.